Hillary Eaton considers how food can both hurt and heal.

There’s no doubt that these have been difficult times and for some people COVID-19 and lockdowns have piled on extra stresses of financial woes, health anxiety, isolation and increased stress at home. While many of us want to support those Kiwis who are doing it tough, especially as Christmas approaches, it’s often difficult to know how best we can help. What is needed most: our time, donated goods or just hard cash? We cannot possibly shine a light on the myriad worthy organisations that are out there getting on with it, but here Hillary Eaton explores The Aunties, an organisation founded by Jackie Clark that provides emotional and practical support to those living with, and healing from, domestic violence. Adopting the role of extended family, The Aunties gives intensive, one-on-one help to those who need it. This support can last for years until whānau are confident enough to take their own steps.

You might ask why Cuisine is bringing you this story. Surely, you might say, Cuisine is about the food and drink of New Zealand. It’s true, we love to share the tales of enthusiastic makers and producers, chefs carving their niche, restaurants and cafés that lift the spirits, and always food, glorious food. But we recognise this comes from a place of privilege: not everyone has the resources, ability or even the interest to access farmers’ markets, artisan products and unusual ingredients, to dine out frequently or share a feast at home. As we head towards the holidays it would be easy for us to just cram our pages with delectable recipes, luscious photos and feel-good stories, but that would ignore that for some people food is a cipher for much deeper, more complicated matters. As the stories here illustrate, sometimes food is part of the problem, sometimes it leads towards the solution. – Cuisine

If you’ve heard of Jackie Clark, you probably know what she thinks about canned tomatoes. Well, it’s not the tomatoes themselves she’s concerned with, but the meaning behind them. Like most things in food, there’s a lot to be found behind the bite.

Jackie is the maternal centre of The Aunties charitable trust, a tight-knit whānau of support for 27 survivors of domestic abuse. In the media, she’s become tied to tinned tomatoes for bringing attention to the overwhelming number of cans donated every year compared to other foods, and, if you read between the lines, the self-gratifying motivation behind certain sorts of giving. In essence, shelters and food banks are often overrun with canned tomatoes as they’re the easiest things to give, while there is a huge need for other quality foods. There’s an allusion to the unfortunate unspoken adage directed to those in need: be grateful for whatever you’re given. Full stop.

This sort of giving is particularly damaging to domestic abuse survivors, who often suffer from very low self-esteem and feelings of worthlessness, feelings that are only affirmed when their worth is mirrored in half-hearted or self-serving charity. Jackie wants better for her survivors, her “shiny f**kers” as she endearingly calls them. Often described as outspoken and unabashedly no-bullshit, Jackie is a special embodiment of love (sometimes tough love) crowned in cigarette smoke and curse-studded speech. She sums it up pointedly: “If you’re given shit, you’re going to feel like shit.” Aunty Jackie is the warrior so many women need.

It’s the structure for recovery – that of an invested whānau giving long-term support – that makes The Aunties unique in the field of the support and recovery of domestic violence survivors. While they don’t help people leave situations of domestic violence (this is for refuges or the police), they focus on working through the long-term effects that domestic violence has on people and their children. “Women have been doing this for centuries,” Jackie says of the model. “Māori and Indigenous women have led the way. It’s not that unique but it seems unique because those women and communities needed to keep things on the down low.” Working in these small whānau groups, Jackie believes, makes all the difference.

“I also speak to about 800 women a year, mainly white middle-class women, who just want to tell someone their story,” she tells me. “They want to be heard.” It causes a story-sized lump to throb in my white middle-class throat.

When we speak about domestic violence, we often focus on the leaving. We ask painfully reductive questions like “Why did you stay?” or “Why didn’t you leave?” to people facing situations as complex as the human heart. Most government support is also focussed on the leaving and the physical and emotional triage of the immediate need. While this sort of support is fundamental for people experiencing domestic violence, there is much less support available for the days that follow. It’s important to recognise that the leaving is just day one. Then the rest of the work begins. “Healing only really starts when you’ve got food in your belly and a roof over your head. When you feel safe,” Jackie explains. “All these things need to be in place or healing’s not going to happen.”

Fulfilling the basic needs of survivors is at the heart of The Aunties and it comes in a few forms. They are always looking for donations of clothes (in good condition only; never second-hand undies), bedding, towels, whiteware and furniture (they are at pains to stress that they do not need your household trinkets). This goes to the whānau and selected refuges and emergency housing. Then there’s the emotional support Jackie provides. Otherwise, much of their ongoing support is in the form of food: groceries so the women of the whānau can feed themselves and their children, removing from the equation the added stress of meeting their basic human needs. Simply, if you have to spend all of your emotional and physical energy trying to cover your basic needs, you have little time for what becomes the unaffordable luxury of healing.

Food and domestic violence have a strong relationship. For many survivors, food is an area of their daily lives that becomes overwhelmingly connected to their abuse. It can be a tool of abuse or a means of coping with abuse. Lack of access to food is also a determinant in the increased likelihood of someone becoming a victim of domestic abuse. Cycles of poverty and abuse are as institutional and old as time. It’s a recipe for “shit soup,” as Jackie calls it.

Jackie will have you know that she is a phenomenal cook. Nevertheless, you won’t find her in the kitchen. During her 22-year marriage, she spent night after night preparing elaborate meals that would only be deemed unsatisfactory. “He never touched me physically, he didn’t have to,” she said. “My friends told me that they would always look for bruises but there wouldn’t ever be any because he never hit me.”

Jackie’s joy from food now comes from restaurants. Cornwall Park Bistro and One Tree Grill are favourites for making her feel special, the most important element for Jackie. “I love Cazador,” she says. “The food is just sublime and the service is so personal and lovely. They remembered my name, for f**k’s sake. That’s so important.”

If food is a basic need to be met in order to begin the healing process, it can also be a piece of the healing process itself. That’s where you come in. Does the feel-good name ‘The Aunties’ inspire you to donate? Then Jackie has succeeded. “It’s used cynically,” she says of the name. “I knew it would give people the ‘warm fuzzies’ and human beings like to fix shit. It’s a self-perpetuating prophecy,” Jackie says. “If you feel part of a community, it becomes that.”

Jackie’s self-ascribed cynicism is for getting the best for her survivors. When we can humanise the 55% of New Zealand women who experience some form of domestic violence, take them out of the abstract and into their individual names and faces, the impact is larger and more intimate. Not to mention the LGBTQ people who are twice as likely to experience domestic violence compared to the New Zealand average, or the one-in-eight men who experience heterosexual partner violence. Plainly, if we know someone, we care – and give – much better.

I tell Tanya* from The Aunties whānau that I know what it’s like to be made to feel crazy by your abuser. “Cool,” she says. “I didn’t mean cool,” she backtracks. “It’s horrible, but you know what I mean.” We laugh (you have to laugh at such things). But I do know. There’s a special security in talking to someone who has been through what you have been through. When you don’t have to explain. Explain things like coercive control, a tactic to psychologically control, abuse and rob a person of their sense of self and mana. Instead, it’s understood, unspoken in the bones, like a different sort of muscle memory: the monitoring, controlling and tracking of everything; the gaslighting, emotional and physical degradation; the cruelly efficient ways of erasing a person. To cope, I disassociated, losing my sense of smell and taste so that food was lifeless. Like pulling the plug of a fan on high speed, I slowed, spinning myself still, inanimate and entirely unhuman.

Tanya and I talk about her new job as a chef. She’s never felt more fulfilled, and was able to pursue it with the support of The Aunties. She’s just devised a Tanya-style sweet and sour pork, the very first dish of her own to go on the menu. I’ve never seen her face, but over the phone I can hear the sound of her smile as clear as water.

It’s The Aunties, the whānau system of support, that can help these women rebuild themselves and their sense of safety in the long term. Then they can mend their particularly difficult relationship to food, one of the most fundamental human rights, pleasures, and forms of community and culture.

The game is long and survivors often don’t realise all that’s been trampled out until it starts to trickle back slowly with time and considerable effort. For me, it was my full sense of smell and taste returning: standing in my mom’s kitchen one night, the oven dyeing the room with the earthy smell of potatoes roasting in their jackets with garlic and rosemary. I hadn’t noticed it was missing until then, but then the smell turned the room comfortably dense, intoxicatingly domestic. ■ * Some names have been changed.

CLARE’S STORY *

“Food and money were withheld and used to get me to do what he wanted,” Clare, a lawyer and survivor member of the whānau, tells me. “I got used to skipping meals so that I didn’t have to ask for things. When we needed something – nappies for my son, food – I had to justify it. Food wasn’t an enjoyable thing.”

Despite Clare’s family being financially comfortable, the kitchen was usually kept bare, with nothing but olive oil, salt and bottled sauces. “Once, I snuck off down the road to go to a shop to buy groceries, but for some reason my card didn’t work.” She recounts being so frantic she wasn’t sure of her PIN and had to leave the groceries behind. When she returned home, she was caught.

Years later, Clare’s relationship to food is shifting with recovery. With the help of The Aunties and support towards buying groceries, she and her children are always fed and she’s tackling the emotions she has surrounding eating and her habit of skipping meals.

“I always include myself in meals now. I can’t say I enjoy food yet or that I enjoy making it. I go to my friend’s house and feel, ‘I wish I was like you’. Dinner is still a stressful time for me. It hadn’t occurred to me that it’s not like ‘once you end the relationship that’s it, you’re free forever’. No you’re not, it’s just the next part of the same journey.”

SCORPION PRINCESS’S STORY *

The first time Scorpion Princess met Jackie she had two black eyes and was holding her baby. She paints her relationship to food during her years in an abusive relationship in one word: addiction.

“I hit 157kg. I didn’t have any energy to do anything for myself. Because my self-worth was so low, the only thing to make me happy was food. If something bad would happen, I would treat myself to something like KFC. It would make me feel better as it was going down, but then I’d get sad, and because I was quite depressed around those times, I was just eating and sleeping. I just got bigger and bigger.”

Wanting to take her power back meant a bariatric sleeve surgery. “When I applied for the surgery I got a good hiding. I wasn’t allowed to do it as he said I’d just start going out and I was just going to leave him.”

After 18 months of hard work, starving herself to reach the surgery’s necessary goal weight to the point of what felt like dying, she reached surgery day 1kg over. “I thought I wasn’t going to get it. I felt so bad about it, but they still let me go through with the surgery.”

She has now lost 60kg. With a supplement of $150 a month from The Aunties to buy groceries, she’s cooking for her children and eating healthy foods. The only catch of the surgery is that many foods she once enjoyed now cause her pain and discomfort, or to vomit.

“I can’t eat reheated food, I can’t eat chicken, I can’t eat onions. I can just stomach yoghurt, two years down the track. But I’ve looked at it like this: I’d rather pay for it this way.” She pauses. “Aunty Jackie showed me I’m worth it. She just loved me – it made me smile. I hadn’t smiled like that in a long time.”

WHERE TO FIND HELP

If you or someone else is in immediate danger, call 111. If it is unsafe to speak, press 55.

For a list of organisations that can help, go to aunties.co.nz/resources

To donate to The Aunties, go to aunties.co.nz/donate

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Inspirational Women in Food & Drink

New Zealand’s food-and-drink industry is filled with hardworking and…

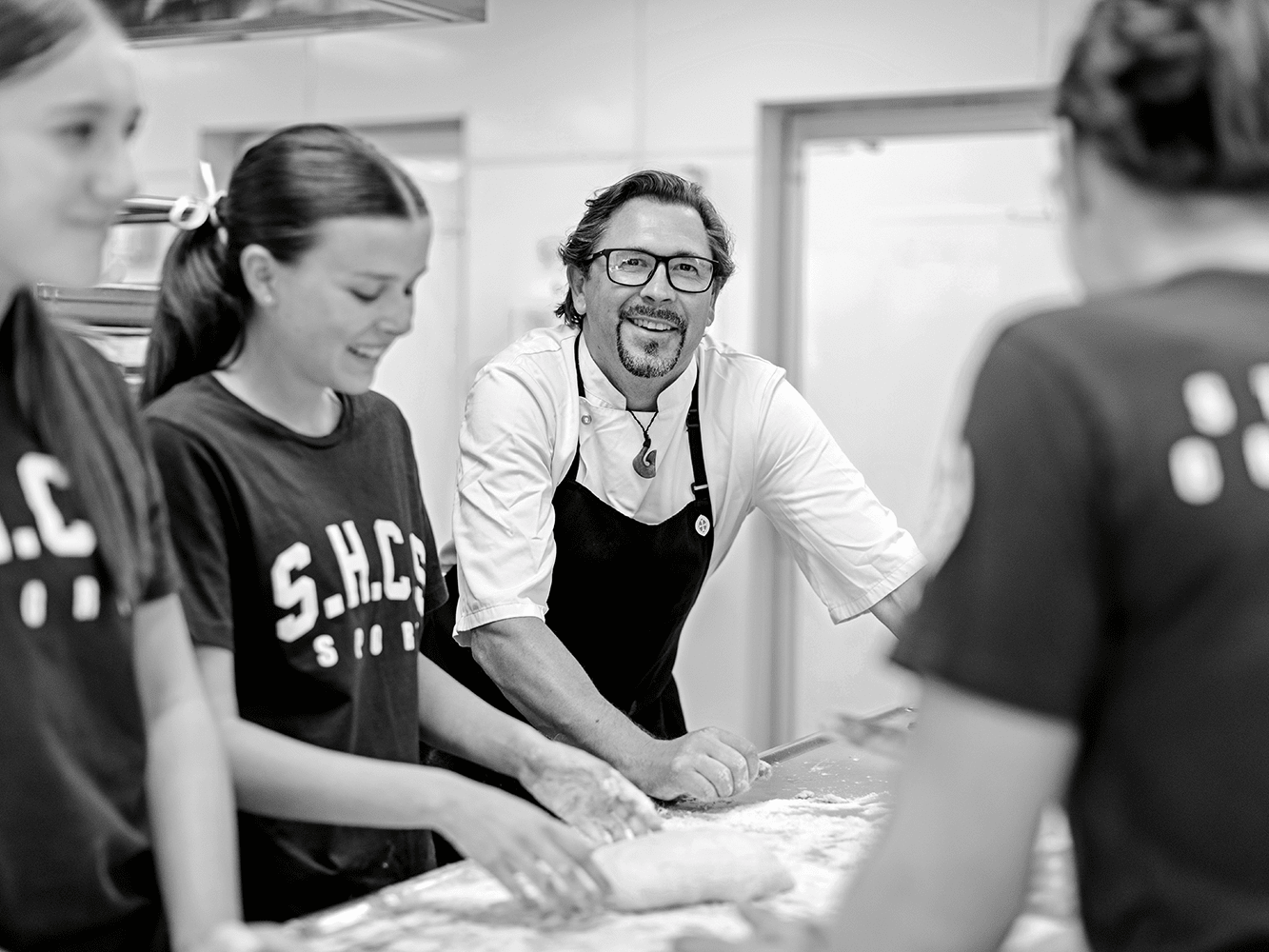

We’ve Noticed…. Marcus Verberne

Cooking skills open up a world of different opportunities. From fine…

Design File / Mark Mitchell / Ceramic artist / Northland

In his Northland studio, Mark Mitchell crafts ceramic pieces that use…