Meatless meat is on the rise – David Burton digs deep into the popularity of plant-based alternative meat.

While vegetarianism and veganism are frequently touted as the great food trends of our time, how many New Zealanders actually identify as vegetarian or vegan? According to a national poll in 2021, a mere 6%. True, this is double the 3% estimate from the New Zealand Vegetarian Society 20 years ago, but it still leaves 94% who continue to eat meat, even if only on rare occasions. And there’s the difference. Whether driven by concern for the environment or for the sake of the health benefits that supposedly accrue, nowadays carnivores are significantly reducing their consumption of meat. A Colmar Brunton research poll in 2019 (commissioned by the vegetarian lobby) claimed 34% of New Zealanders are flexitarians (those who have a primarily vegetarian diet but occasionally eat meat or fish) or meat-reducers.

THE ‘WHY’ OF PLANT-BASED MEAT

As many people, millennials and Gen Z in particular, embrace the flexitarian lifestyle, adopting plant-based protein – most fashionably known as alt-meat – gives them the option of not missing out. They can still have the burger-eating experience, while addressing environmental, health, and animal welfare issues.

So if you could be convinced that the meaty, juicy plant-based burger patty in front of you was going to taste uncannily of beef and yet be assured that no animal had died in the process, why wouldn’t you tuck in?

Being large consumers of fast foods, millennials and Gen Z are being targeted by the big three: McDonald’s, Burger King and KFC have all introduced plant-based meats. Interestingly, KFC, recognising their core market as flexitarian, have announced that their alt-chicken will be cooked using the same equipment as the real chicken.

When it comes to marketing the products, should an image or illustration of an animal be featured on the label of a product that is not made from an animal? If so, I’m not sure how the contents might comply under the Fair Trading Act, but certainly back in 2018 the French government saw fit to ban depictions or even mentions of animals on packets of imitation meat.

A MATTER OF TASTE

On the shelves of the newly named flexitarian section at my local supermarket, I found a wondrous array of this new breed of highly processed ‘meat’. At home, armed with a selection to taste, I unwrapped my first pink flesh-toned strips. Resembling rubber, with natty streaks of cartoonish faux fat, they look more like a toy I might buy for Pablo, my pet chihuahua. There was a mildly repugnant chemical odour when I first opened the packet, which finally dissipated into a smoky aroma as the ‘rashers’ were frying. Eventually I realised the offending smell must come from the copious ‘smoke flavouring’ listed among the ingredients, there to stand in for the missing bacon flavour. As my wife Andrea pointed out shortly before spitting out her first mouthful, the mushy texture closely resembles ox tongue. She hates ox tongue. Offered the half-eaten packet, Pablo caught one whiff and backed off. Eventually we binned it.

The texture of the next plant-based rasher was even worse. When I tried to lift the outside edges of these oversized sticking plasters with a paring knife, they crumbled. No wonder the product cooked to a soft, mealy texture.

Next up was a rasher whose texture, for a start, did not come anywhere close to that of real bacon. The ‘rasher’ bubbled up and exuded a mystery frothy white substance during frying, albeit a pleasantly flavoured froth, which ran over the side and into the pan. Once again, smoke essence stands in for bacon flavour.

Onto the chicken: after deep-frying as per the packet instructions, in texture there was some similarity to chicken – overcooked, dried-out chicken – but in flavour, none at all. Funnily enough, however, the deep-frying seemed to lend it a faint suggestion of pork crackling.

For me, two of the four brands of plant-based sausages that we tried fared better than the others. The first – once you got past their condom-like casings – tasted vaguely realistic, as did the second. But in every case Andrea ate one, pronounced it yuck and left the rest on her plate.

However, distaste soon turned to praise when we tried two plant-based burger patties. “Hmmm, really good!” Andrea exclaimed when biting into her first patty. The next was even more convincing. Juicy, with a true mince-like texture, it came uncannily close to a true meaty taste with iron flavour notes, albeit blander than real beef. On the taste intensity scale, it might be mistaken for fillet steak, rather than a hearty secondary cut such as brisket.

IS IT HEALTHIER THAN MEAT?

I turned to the ingredients listed on my first burger and realised that had I not been sold on it being a clever meat substitute, I might not have necessarily chosen to dine on pea protein isolate, expeller-pressed canola oil, refined coconut oil and methylcellulose.

That the canola oil is expeller pressed is laudable, since this is a healthier alternative to the standard industrial method of bleaching the canola oil to remove the rancidity that inevitably occurs during manufacturing. However, the package ingredient list does not specify non-GMO canola oil, which is significant since most canola oil is now made from genetically modified rapeseed.

Both alt-meat patties contain coconut oil. Despite it having enjoyed a vogue a few years back, we now realise coconut oil contains 80–90% cholesterol-raising saturated fat.

Methylcellulose, a thickening agent found in both of these burgers – as well as in a number of other alternative meats seeking to replicate a meaty texture – is typically extracted from wood chips heated in a chemical solution and treated with methyl chloride. It’s indigestible, yet apparently safe for human consumption.

One leading brand – the Impossible Burger – even ‘bleeds’ like a real beef patty when correctly cooked medium rare. But the catch is that this trick is a result of genetic modification. As the world moves to feed its population in future, perhaps we will have to get used to the idea of genetically modified crops to ameliorate the effects of climate change and to reduce the need for pesticides. In any case, Impossible Foods unapologetically admits to having injected fermented yeast with the DNA of heme, the flavour molecule that lends beef its meaty, faintly metallic taste.

But before having doubts about the highly processed nature of some artificial meat products, consider that the products they are aiming to stand alongside – the meat-based burgers, sausages, bacon and chicken – may also contain an equally long list of additives or difficult-to-interpret ingredients.

And, one thing is for sure, replacing your favourite protein with a plant- based option is not going to improve your diet if you order fries alongside and wash it down with a soda.

ARE WE SAVING THE PLANET?

The World Wide Fund for Nature says demand for soy (the key constituent of many alt-meats) has led to deforestation, which means more greenhouse gases. What does this mean for people who decreased their meat eating due to concern about meat- related emissions causing climate change? Most sheep and beef farming in New Zealand takes place on rolling or hill country farms, unsuitable for growing crops. Might pasture therefore be the best use for this land?

ARE WE SAVING MONEY?

You certainly wouldn’t be buying alternate meat to save money. At around $40–$50 per kilo, most of these products are more expensive than fillet steak. However, Christchurch company Berkano Foods recently launched an imitation chicken product at $19.90 a kilo, and there are indications that alternative protein will become still cheaper in future – Stanford University economist Tony Sebo predicts 10 times cheaper than meat by 2035. By then, will our alternative protein still mostly be artificial meat? Recent indications are that the alt-meat trend may be passing: from 2018 to 2020, the US alt-meat market shot up by 64% to US$1.4 billion, but last year it levelled out completely.

As environmentalists and food scientists advise us to eat more plants and less processed food, perhaps one way forward would be to focus on flavoursome, wholesome new products that unashamedly showcase protein-rich grains, or dishes that celebrate the flavour of veges themselves, without trying to replicate the characteristics of meat – you’ll find plenty of such delicious recipes in this issue.

So, while attributes such as health, ethics and convenience go far to drive consumption of plant-based meat alternatives, ultimately their success comes down to taste. ■

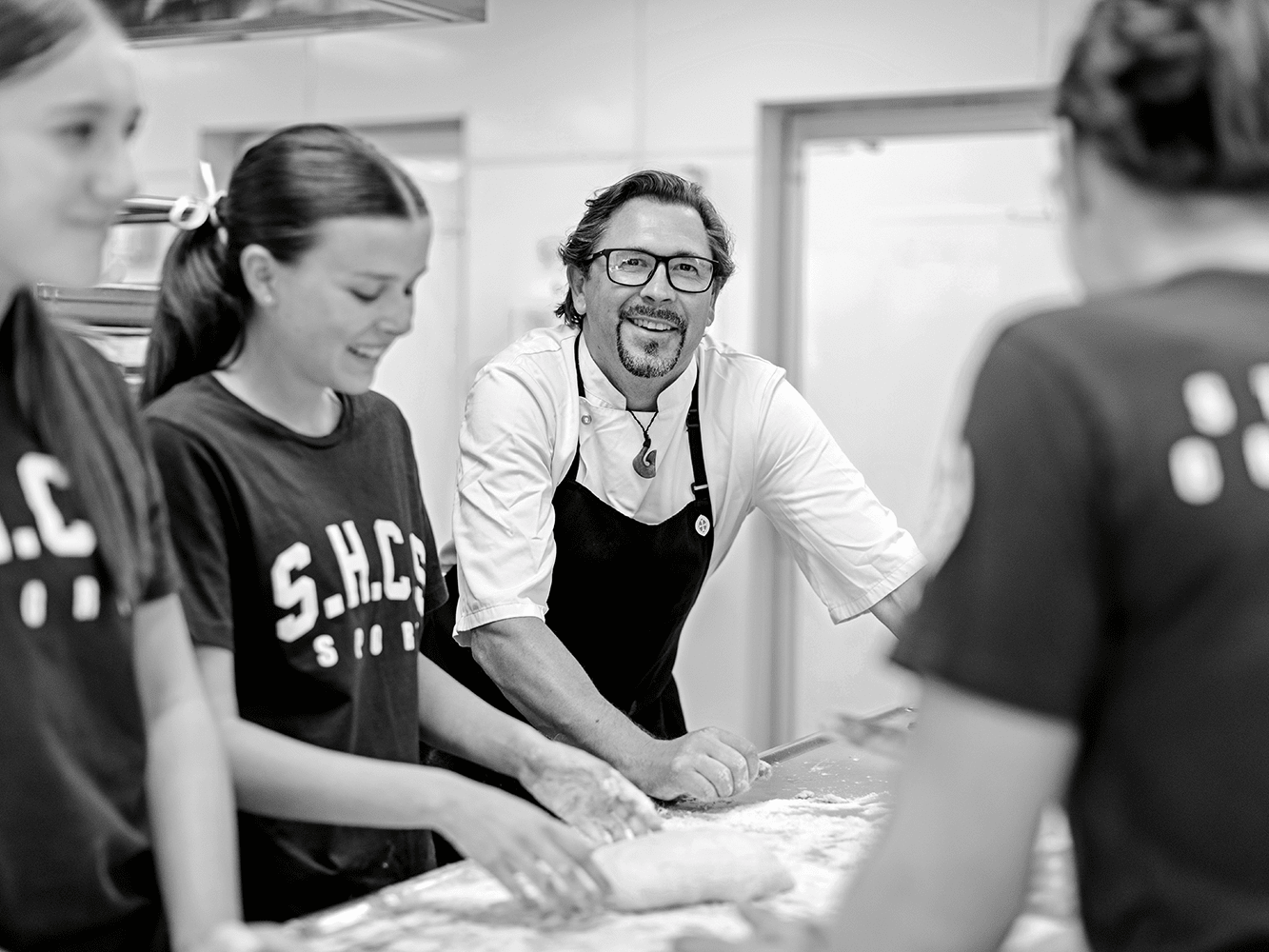

'Kelli Brett cooks alternative meats alongside the real deal for three intrepid taste testers...'

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Inspirational Women in Food & Drink

New Zealand’s food-and-drink industry is filled with hardworking and…

We’ve Noticed…. Marcus Verberne

Cooking skills open up a world of different opportunities. From fine…

Design File / Mark Mitchell / Ceramic artist / Northland

In his Northland studio, Mark Mitchell crafts ceramic pieces that use…