David Burton gets to grips with the grassroots facts behind our beef, lamb, pork and chicken innovators enabling New Zealanders to make a concious choice

Increasingly, the New Zealand meat industry is under fire, despite the fact that, by even the most conservative estimate, 85 per cent of New Zealanders still eat meat – and so many benefit from an economy that continues to depend on it. The sector is our second-largest merchandise exporter, generating $12 billion in income per year and contributing $3,300 annually to every New Zealand household.

Our rain-fed pastures are eminently suited to raising animals and, indeed, are useful for little else: according to the Beef + Lamb New Zealand Economic Service, 93 per cent of our sheep and beef farmland is not suitable for growing crops due to steep or rolling hills.

Beef: grass-fed versus grain-fed

Until recently – only about 10 years ago – grass-fed beef was anathema on the world market. In the US, where consumers are accustomed to the taste of grain-fed beef, they felt grass-fed meat lacked flavour and was less tender. Of course, that’s because a lot of the flavour is in the fat and our beef is more lean. But environmentally and ethically speaking, grain-fed beef (especially US corn-fed beef, with its feedlots reportedly full of bloated, gaseous cows) just doesn’t stack up.

Raising cattle on pasture is clearly more sustainable than grain-feeding, since it takes between 8 and 10 kilograms of grain to produce 1 kilogram of beef. Grain-fed beef accounts for just 1.5 per cent of New Zealand’s production (two feedlots, owned by ANZCO – Wakanui and Ocean Beef – still operate this way), and it’s likely to stay like that given the high cost of grain in Aotearoa coupled with ongoing pressure from the vegan lobby group SAFE. In a pioneering approach, even our First Light group of farmers crossed its Wagyu cattle with Angus cattle to enable grass-feeding.

Grass-fed is emerging worldwide not just as ethically superior, but possibly healthier too with the proportion of good omega-3 to bad omega-6 fat in grass-fed beef proving measurably higher.

In the US, the number of grass-fed beef companies has grown from 10 four years ago to around 70 today. And, while virtually all New Zealand’s grass-fed beef was formerly ground into hamburger meat, these days, on the eco-conscious western and eastern seaboards especially, it is reaching table-steak status.

The Silver Fern Farms co-operative, New Zealand’s leading meat processor, has been quick to take advantage of these export opportunities, promoting its Eating Quality System, where its master graders choose the prime-quality beef carcasses according to low pH, good fat marbling, good cherry-red colour and lack of ossification (the conversion of cartilage into bone with age).

Good pH levels and meat colour are both achieved by minimising stress, which is why on the farm, any good finisher keeps the same close-knit mob of cattle together for two months before sending them off to the works.

Fat marbling and ossification are partly related to diet, so it is in the farmer’s interest to raise cattle humanely and quickly on lush green pasture.

The ‘grass-fed’ labelling can be seen on Silver Fern Farms’ meat packs in our supermarkets. These meat packs also carry the Oritain seal, certifying their New Zealand origin, which might not seem necessary until you realise that some steak sold here comes from Australia, where mixed-feed regimes are the norm.

Te Mana lamb

Alliance Group, which processes and markets Te Mana Lamb, takes traceability one step further by arranging special shifts to process the lambs at its plants near Invercargill, Timaru and Dannevirke.

A partnership between Alliance, a group of progressive farmers known as Headwaters and the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), Te Mana Lamb comes from a composite animal developed by Headwaters, which has Romney, Finn, Texel and Perendale genetics. The lamb challenges the trend towards leaner lamb with a meat that is fattier.

However, the important difference is that these are good fats: the breed is higher in polyunsaturated fats instead of the unhealthy saturated fat. These fats have triple the usual amount of desirable omega-3, and they are marbled throughout the flesh, making the meat tender and more forgiving of overcooking.

The Headwaters breed was born of a plan to ensure sheep on the South Island’s high-country stations could thrive. Modern lean sheep would struggle, so the Headwaters sheep were bred to be healthier, handle the tougher conditions – and taste better.

You might think that such breeding conditions would add up to stronger-flavoured lamb, yet the opposite is true: Te Mana is some of the mildest-tasting lamb available, due partly to the animals having been finished on chicory pastures.

Coastal Spring Lamb and Coastal Lamb

Like Te Mana lamb, spring lamb tastes noticeably milder due to its diet of mother’s milk and the lush pastures of spring. Later, the gnarliness of the dry summer pasture introduces a stronger, more agricultural flavour to the flesh. Being from a young animal, the meat is lighter in colour and has a sweeter taste and, since its sinews are not yet fully developed, there is less waste involved in trimming.

At one time, spring lamb was a big deal in New Zealand, and butchers would write in white paint across their shop windows: “Spring lamb has arrived”. Now, spring lamb is once again branded as such by the 17 farmers who combine to offer Coastal Spring Lamb.

Coastal Spring Lamb lasts from October to late January. Then from February to September it becomes Coastal Lamb and is fed on crops of chicory, lucerne and clover, designed to speed up the growth of the lamb and improve the flavour. Each lamb is hand- selected by feeling its ribs for fat cover.

More crucial to the quality, however, is the fact that all 17 of the farming families in the group have farms on coastal land around the North Island, meaning their grasses are naturally salted by the sea breeze. Tests by Massey University on Coastal Lamb founder Richard Redmayne’s farm show that his soils have twice the sodium level of an inland farm near Taihape, while his grasses have four-and-a-half times as much sodium and nine times as much iodine.

The theory, Richard explains, is that both the sodium and the iodine aid water retention in the cell tissues. This makes the meat more tender and juicy, while the sodium has the effect of seasoning the lamb or ‘pre-salting’ it – a phenomenon well known to French consumers, who are prepared to pay a premium for such pré-salé lamb from Mont-Saint-Michel in Normandy.

Pork: free-range versus free-farmed

For those who can afford it, free-range pork might seem the obvious ethical choice. However, since the term ‘free-range’ is not protected by law in New Zealand, many restaurateurs, café proprietors and food-truck owners take the liberty of describing their pork as ‘free-range’ when in fact they mean ‘free-farmed’.

There’s an important difference. True free-range pork means the meat of a pig that spent its entire life outdoors, with adequate feed, water and individual huts for shelter.

Free-range pork does not refer to animals that were born outdoors but then taken away from their mother once weaned at four weeks and reared in large, partially open-sided barns (sometimes euphemistically referred to as ‘deep-straw shelters’), which can hold 500 or more pigs. That is free-farmed pork.

Large Black and Duroc (ginger) pigs at Woody’s Farm.

Large Black and Duroc (ginger) pigs at Woody’s Farm.

Part of the reason that free-farmed pork is often passed off as free-range is that the genuine product is in such short supply. True free-range pork accounts for only about one per cent of New Zealand’s production and comes from just a handful of farmers: Poaka in South Canterbury, Farm Gate Produce in Houhora near Kaitaia (which sells online and at the Parnell Farmers’ Market in Auckland), Highgrounds in South Canterbury (who supplies the Harmony brand), Havoc Farm Pork near Dunedin and Longbush in the Wairarapa.

Longbush sends the vast majority of its output to Woody’s Free Range Farms’ purpose-built dedicated butchery operation in Levin, which it owns in conjunction with Daniel Todd, who formerly ran Woody’s free-range pig farm there.

Nowadays, Daniel is a charcutier, working with a special quality of marbled pork from heritage pig breeds such as Large Blacks, Berkshire, Hampshire and Duroc, which date back to before the Industrial Revolution and are hardy enough to survive outdoors. They are slower to grow, but from a gastronomic point of view their meat has more muscle and is made more moist by a good degree of intramuscular fat marbling (the Berkshire in particular).

Chicken: industrial ‘free-range’ versus organic free range

As with pork, ‘free-range’ chicken can refer to some very diverse farming operations, and a ‘free-range’ chicken bought from one of the big industry players might not coincide exactly with the popular understanding of the term.

Certainly, the shed that houses an intensively farmed free-range chicken has small doors along the side, which allows the chicken to go outside for the final two weeks of its life. But there are no limits on flock sizes of free-range chickens in these large conventional operations, meaning that 40,000 birds might be housed in just one shed.

In contrast are the chickens produced by New Zealand’s only organic free-range producer: Bostock Brothers in Hawke’s Bay. Organic farmers are limited to just 6,000 chickens per shed. Some of the Bostock 36 sheds hold just 2,500 chickens and their weekly output of 15,000 chickens contrasts dramatically with the 500,000-odd chickens delivered by a big conventional free-range farm each week.

Aside from ethics, there are gastronomic advantages to a chicken raised on a better diet. A Bostock chicken is fed the apple pomace left over from juicing operations, as well as organic grain, also grown on the farm. In addition, a Bostock chicken eats grass and insects it grubs up from the pasture. Perhaps most significantly, a Bostock chicken is raised for 50 days as against 30 for a conventional operation.

“At Bostock Brothers we grow our chickens longer, so the meat has more time to form and as a result has more flavour and is superior tasting,” says George Bostock. The greater density in the flesh is palpable: a Bostock chicken breast typically makes a squeaking sound as a knife is sawn through it.

Over and above the superior texture, a Bostock seems to have a deeper ‘chickeny’ flavour, much like France’s famously expensive poulet de Bresse.

Game: the ethical meat

Wild game meat is, by definition, organic. Only healthy animals survive in the wild, and they’ve had no dips and drenches. More significantly, game meat enjoys the ethical high ground: by eating the pests that are decimating our native forests, the consumer is doing the environment a favour.

Eating possum might almost be our most pressing duty, were it not for the fact that tuberculosis infection among possums is rife and the MPI has declared their meat unfit for human consumption.

We also ought to be eating wild tahr, not just because their numbers are of concern to the Department of Conservation (DOC), but also because their meat is delicious, tasting somewhat like goat.

Then there’s the issue of wild deer, particularly as numbers are rising again in the wake of a global oversupply of venison, which has forced the closure of several deer abattoirs in recent years.

These export-led venison abattoirs have been part of the New Zealand landscape since the late 1960s but, since its inception in 1996, Blenheim’s Premium Game has always set out to serve the local market. It is still our biggest player.

All hunters working for Premium Game must be licensed with the MPI and ensure their game is chilled within 10 hours of it being shot. If Premium Game itself is doing the shooting, it will send along a ute towing a registered chiller as a trailer. Once back at Premium Game, the carcasses are checked by MPI meat inspectors for disease and correct presentation (heart, lungs, liver, kidneys still intact).

Co-owner Darren Clifford says about 35 per cent of Premium Game’s sales are to the hospitality industry; alongside the venison and pork you might expect, goat meat accounts for a surprising 30-35 per cent of their sales. This is partly because of the immense popularity of goat curry at our Indian restaurants, but also because of increasing immigration from countries where eating goat meat is the norm.

That said, Darren believes the increased adventurousness of ordinary home cooks as well as concerns with provenance are driving the rising sales of their home meat packs.

The future: lab-grown meat

Those invested in the future of lab-grown meat (or ‘cultivated meat’ as they prefer to call it) claim that price parity with farmed meat is achievable within five years. In the early stages, fetal bovine serum was used as the growth medium for the cell cultures, but this is now considered economically unviable and alternative growth media are currently under investigation.

Dutch consultancy CE Delft more conservatively puts the price parity date at 2030. Meanwhile, Fonterra already has a small stake in a US-based company that bioengineers animal ingredients. Whenever it arrives, cultivated meat is an inevitability, so what happens to our meat industry after that? As New Zealand is already catering to a niche market of luxury restaurants around the world, there seems little doubt this trade will continue.

In future, will it only be the very rich who will be eating real meat while the rest of us make do with the cultured version? Only time will tell.

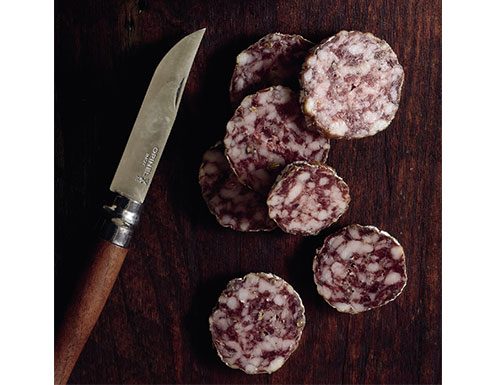

SALAMI HEROES

Apart from ham, bacon and sausages, there is no inherited Anglo-Celtic tradition of charcuterie in this country, and a great many New Zealanders have never experienced the deeply complex flavour of authentic European salami. This possibly explains why Australasian mainstream salami and bierstick producers are able to get away with selling us such cheap imitations, made by adding soy to bulk out the meat, acidifiers to compensate for greatly sped-up fermentation processes, and phosphates to bind the water to the meat, thus reducing moisture loss for the sake of boosting profits. However, we do have a small band of artisan producers dedicated to making salami in the same painstaking way as their counterparts in Italy and Spain, by using a starter culture to ferment the raw pork, and then ageing the salamis for up to two months. By this stage they have shrunk, losing up to 40 per cent of their weight through evaporation, yielding a slightly tangy, totally delicious flavour.

POAKA

Uniquely, Josh Hill’s Berkshires, Wessex Saddlebacks and Tamworths are finished on acorns in the tradition of Spain’s legendary jamón ibérico, as well as chestnuts grown on his father’s Canterbury farm. About 90 per cent of his output goes into making superbly complex salami in the southern Italian style.

WOODY’S

Because he is ideologically committed to using every part of every pig that arrives from Longbush Farm, Daniel Todd turns out a mind-blowing variety of smallgoods, including steamed mortadella and traditionally fermented and cured salami.

THE HUNGARIAN ARTISAN CO

Based at Te Puna on the outskirts of Tauranga, Hungarian-born chef Attila Kovacs and his English-born partner Samantha Darragh use recipes that have been in the family for hundreds of years. Hungarian salamis and Goan chorizo are made with free-range pork and involve traditional salting, smoking and dry-curing for four or five weeks. Eschewing fillers and artificial ingredients, the only base flavourings are paprika, garlic and cumin, sometimes with additional Kashmiri chilli, porcini, truffle, pink peppercorns and fennel seeds.

THE BLACKBALL SALAMI CO

While some early Dutch producers (such as Bells) did make honest salami for New Zealanders for a period in the 1950s and 60s, the modern pioneer was Pat Kennedy, who in 1992 opened his tiny salami factory at remote Blackball near Greymouth. Current owners Phil and Debbie Russ still offer Pat’s original lean venison salami, but now also cure Italian-style salamis with added fat.

MARTINEZ CHORIZO

Martinez is named for charcutier Vaughan Stanley’s late father-in-law – Spanish restaurateur Manuel Martinez. Vaughan trained as a chef in Switzerland and formerly lived in Spain with his wife Nadine. The Cromwell-based couple import their own smoked Pimentón de la Vera directly from growers in Càceres, and their naturally cured chorizo is guaranteed to spoil you for those other New Zealand-produced ‘chorizo’, showing little paprika flavour and mistakenly made fiery hot.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Inspirational Women in Food & Drink

New Zealand’s food-and-drink industry is filled with hardworking and…

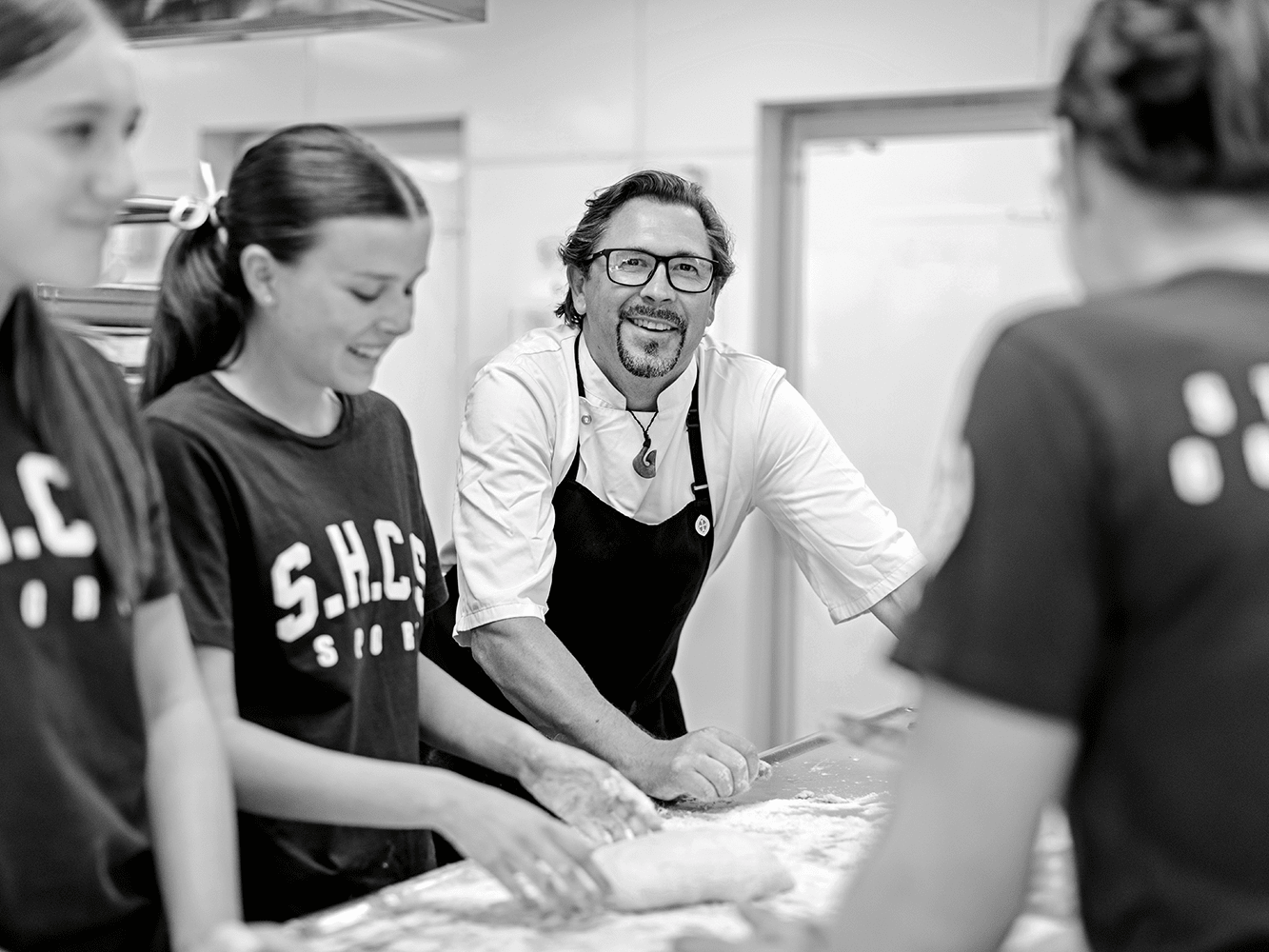

We’ve Noticed…. Marcus Verberne

Cooking skills open up a world of different opportunities. From fine…

Design File / Mark Mitchell / Ceramic artist / Northland

In his Northland studio, Mark Mitchell crafts ceramic pieces that use…