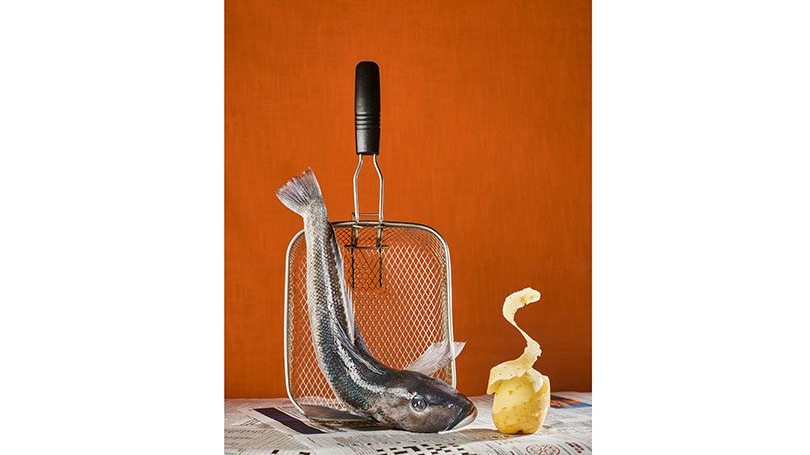

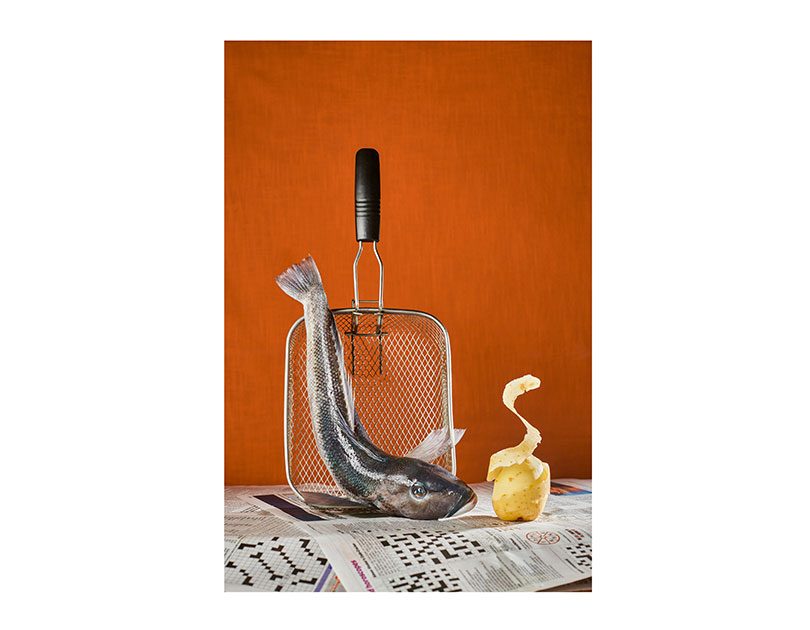

Martin Bosley investigates what’s actually in your fish and chips?

A quiet Friday night on Main Street with the scent of cooking fat hanging in the air, punctuated by the sharp, high notes of frying potatoes and, through it all, the punch of freshly cooked fish. This is a tradition deeply embedded in our culture: queueing at the fish and chip shop, reading the business cards pinned to the wall; playing the ancient arcade games; hoping for a batter that is crisp and will stay crisp until we get home, the fish inside perfectly steamed, the flakes sliding away from each other. But can we be sure of what the fish we are eating actually is?

A recent article in The Guardian raised the disturbing issue that fish and chip shop customers in South Australia are eating threatened and imported shark species labelled as ‘flake’, with less than a third of servings meeting seafood labelling standards. The Australian Fish Names Standard states only two types of shark – gummy shark and New Zealand rig – should be sold as flake in Australia. Other shark should be labelled according to its species. Consumers are buying flake, thinking it’s a sustainable option when sometimes it’s not. It is entirely possible that the fish and chip shops had bought the fillets without knowing their true origins as they simply want the cheapest flake they can buy. “Passing off any shark species as ‘flake’ is like passing off red meat from cows, pigs, lamb, horses and kangaroo all as beef,” the article states. “Consumers have the right to know where the flake is coming from.” (“Endangered shark sold as flake in South Australia fish and chip shops, study finds”, The Guardian, 24 Jan 2023).

All of this begs the question, what do we know about the provenance of the fish in our own fish and chip shops? Can your local chippie tell you where it’s from and what it is? Mine certainly can’t – year-round he simply calls everything ‘warehou’, which has probably been frozen at sea and is possibly at least six months old. Surely, when we are being encouraged to ask this question in our restaurants, we need to extend the question to our most popular of seafood eateries.

Once upon a time, our fish and chip shops sold predominantly rig or lemonfish, both sharks renowned for their cheap price, flavour and ability to stand up to being cooked at 185 ̊C.

As time has moved on and fish and chip shops have evolved, it is now more likely to be elephant fish, warehou, moki, trevally or gemfish. Recently – horrifyingly – despite our oceans teeming with sustainably caught fish, two new entrants have made their way into the frying baskets of the nation’s favourite takeaway: the imported species basa and tilapia. Both are a type of freshwater catfish, farmed in pens along the Mekong and Chao Phraya rivers which run through many Southeast Asian countries. Cheap and flavourless, imports of these fish into New Zealand have increased in the past five years.

Pardon the pun, but we need a sea change in the way our fish and chip shops present their fish. We have a world-class inshore seafood fishery that employs thousands of people. As consumers we need to get into the habit of asking what the fish is, where the fish is from and if the seller doesn’t know, then buy something else.

(Editor’s note: In the March 2021 issue of Cuisine, we asked you to nominate those fish and chip shops that were sourcing their fish sustainably – see issue 204).

ASK HOW YOUR FISH WAS CAUGHT

PURSE SEINE

Uses a net to herd fish together and then envelope them by pulling the net’s drawstring.

LONGLINING

A long line is set and dragged behind a boat to catch fish on baited hooks.

SPEARFISHING

The diver views and selects each fish before the trigger is pulled.

POTS

Use baited traps and have low impacts on bottom habitat.