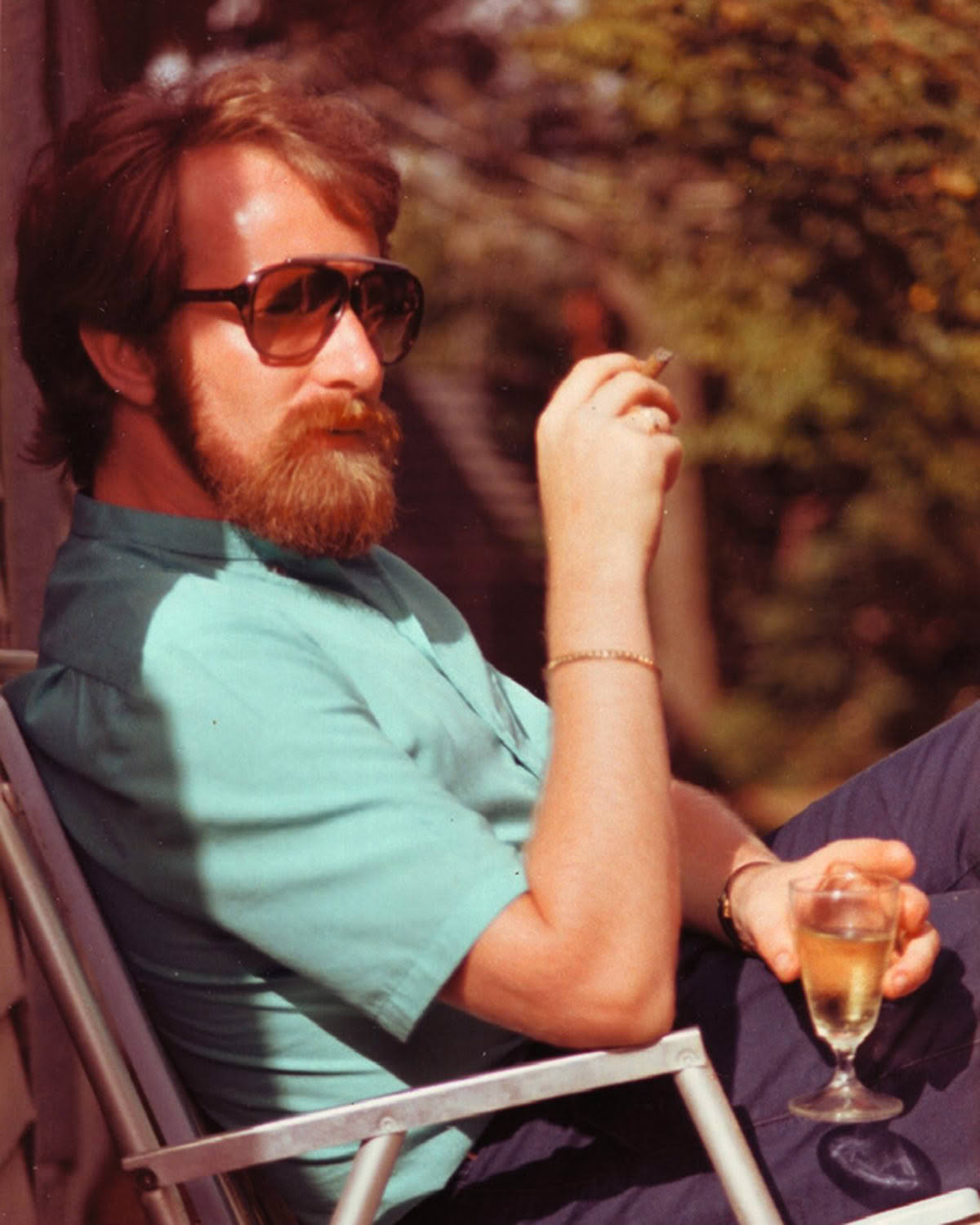

Tony Astle at Antoine’s

So, here I am at the ferry terminal on Aotea Quay. I have left my home and family in North New Brighton. I have a suitcase, a coat and nothing else to my name – not even one scholastic qualification. (Much to the horror of my parents, I didn’t even wait to sit School Certificate before I exited Shirley Boys’ High.) My South Island life has ended and a new world awaits me in Wellington. I do not know a soul, but I do know why I’m here. Mum had only let me go because I’d written to Graham Kerr in search of work. I can’t remember exactly what I said, but it was something along the lines of: ‘Dear Mr Kerr, I have watched your television show with great admiration. I myself would like to cook like you and I wondered if there were any opportunities to get me into the kitchen?’ I may have mentioned my Rotary Honour Roll Award. Who knows?

Whatever I said, it worked. Kerr had a cooking school called Kerr’s Gourmet International School, and he also knew Madame Louise at Le Normandie. The deal was that I would go to Kerr’s cooking school and also work at Madame Louise’s restaurant. I was to board at the Salvation Army Hostel, Rudman House, in Vivian Street. Sorted (or so Mum thought, at least).

The school was in the International Trade Centre on Cuba Street. The tutor was a woman called Rosemary Clarke – a Le Cordon Bleu-trained chef who had come back from London specifically to take up the position. She was probably the first woman with a Le Cordon Bleu qualification to teach in New Zealand, and she taught me a lot. I’d work at nighttime at Le Normandie, which was below the International Trade Centre, and go to school in the daytime.

Spotty, skinny me was the only boy in the cooking class; a Mr Chan (he already owned a chain of Chinese restaurants in Wellington) was the only man. All the other students were women, because that’s what Le Cordon Bleu was all about in those days. However, it was a good learning curve, both professionally and socially.

Right at the beginning, I was hooked. It wasn’t just the food that I fell for, either. I was suddenly meeting people who had lives the likes of which I had never known before. My working-class family life had been pretty unremarkable, and I hadn’t been to university, so for me, once I left school, all I did was work and sleep and work and sleep. I had an idea of how ‘the other half lived’, I suppose, but once I saw that other side – the glamorous side – for myself, I decided I wanted to be part of it.

In the beginning, I worked at Le Normandie six nights a week and went to cooking school on weekdays. I had a cute little waiter’s uniform at the restaurant, and I learned how to keep it perfectly pressed without the aid of an iron. Every night in the hostel, I’d put my long fancy pants between two sheets of newspaper, and then slot them between two sheets of hardboard. I’d slip the wooden sandwich under the mattress, climb into bed – and hey presto!

Madame Louise was formidable. A large, imposing woman, she had dark-red hair piled up on top of her head. It was a scary sight for a boy in her employ to behold. She didn’t trust me in her kitchen at first; she determined I would instead start as a waiter. But she was such a tyrant, she kept at me all the time: It was ‘Work! Work! Work!’ (Which I suppose was good – or even if it wasn’t, at least it taught me how to operate front-of-house.) And she never called me by my name, it was always ‘Little One’. (She pronounced it ‘Leetle One’.)

Le Normandie was rather baroque. It had flocked wallpaper and floor-to-ceiling drapes. It had crystal chandeliers casting light over plush velvet banquettes. And secrets. There was an alcove in the wall that had ornamental pots sitting in it. But secreted behind them was a little hole – Madame Louise’s spy hole. She used to sit in the alleyway that ran alongside the restaurant and watch everyone in the dining room – so, no matter what you did in there, she knew what you were up to. She used to watch me serving, and then if I did anything wrong, I’d hear her scream: ‘Leetle One!’ from the back, and I’d have to run out. I was truly terrified of her. By way of punishment, she’d dole out duties like washing the windows – all of them.

But I was charmed by restaurant life. This was my introduction to the world I had hankered for. One of my first such introductions was to John Buck – later winemaker and chairman of Te Mata Estate Winery. He was doing the wine course at Graham Kerr’s school, which I also did. The woman who became his wife, Wendy, was my best friend. And here we are, nearly 60 years later, and still our friendship continues.

As I settled into my Wellington world, I began to widen my social coterie. After I finished my shift at Le Normandie, I’d sometimes wander up Cuba Street and then down Vivian Street, to places like The Purple Onion and Carmen’s International Coffee Lounge. This was Wellington’s red-light district: The Purple Onion was the city’s first drag bar; Carmen’s was the home of legendary drag queen Carmen: aka Trevor David Rupe. Well, I used to go knocking on the doors there, looking for coffee. At first, I wondered why the women there would say ‘Hello, darling’ in such deep voices. A boy from New Brighton didn’t know anything about drag queens – but of course that’s what they all were. They’d take you in and were always remarkably kind. It wasn’t quite a ‘Lola’ moment, but I got to know them. I’d go in there and they wouldn’t let me have alcohol, but they’d give me coffee on my way home. I later learnt that a lot of the coffees in these unlicensed establishments had grog slyly tipped into them. And the positioning of the empty coffee cups (face up, sideways or underneath the saucer) indicated one’s sexual preferences. But back then, things were much simpler for me. So, that’s how I first met Carmen and her mates.

Even on my one day off, I could not escape Madame Louise. On the seventh day, she would take me out to the White Heron Lodge in Kent Street, Kilbirnie, where I met Otto Groen, who was running it. Madame believed the White Heron was the place where I should get my training in eating and drinking, and she’d chosen well: Otto had been awarded the country’s first restaurant liquor licence in 1961. Later, he would set up a few notable restaurants of his own in Auckland.

I met some other big-name chefs while I was there, Peter Bowald among them. I was also getting a very pleasant introduction to Mr Alcohol. By then I was tiring of life at the Salvation Army Hostel, and I think they were probably tiring of me. They’d lock the doors at 9 o’clock at night, which isn’t very conducive to a good night out when you’re 16 years old. And of course, the inevitable happened. One night I got very, very tipsy after work. When I got dropped off at the hostel, the place was locked and in darkness. And I had forgotten my key. So I decided to climb up the fire escape to my room on the top floor. My bedroom looked over the Sallies’ home for alcoholics next door – which the hostel major always used to suggest would be my destiny if I didn’t stop drinking. My drunken late-night attempt at a discreet re-entry failed spectacularly: I made enough noise to awaken the major – and probably the rest of the street, if the truth be told – and somehow he managed to meet me at the top of the fire escape at the same time as the contents of my stomach decided to re-emerge. Things were not pretty. Then they did a spot-check of my room and – horrors! – they found alcohol hidden under my bed. Did I jump or was I pushed? Whatever way you look at it, I was leaving Rudman House after that.

I decided I wanted to go flatting, but my efforts to secure new digs truly illustrated my naivety. Remember, these are the days when classified ads were the internet equivalent. So, what did I do? I went and placed an advertisement in the newspaper: ‘Sixteen-year-old youth requires flatmates or board’. Talk about meat to the slaughter.

Talk about a bit of bait. Suddenly the phone started ringing. I’d given Le Normandie’s number – you didn’t ring the Salvation Army. So I set up all these meetings, and soon I was encountering a string of men who picked me up and took me to their houses and showed me their rooms. Naturally, I was oblivious to their intentions. It makes me squirm to think of it now.

There was one particular incident that sticks out in my mind. Off I went to this address and this guy… well, he jumped me, or tried to, and of course I ran away.

I am eternally grateful for the fact that I could turn to and trust another Le Normandie waiter – an elder of the establishment. José Hernandez – who we later crowned the ‘King of Spain’ for his contribution to the wine industry in Auckland – heard my account, and he decided: ‘Young man, I’m taking you under my wing. Otherwise, you’re going to be in trouble.’ ■

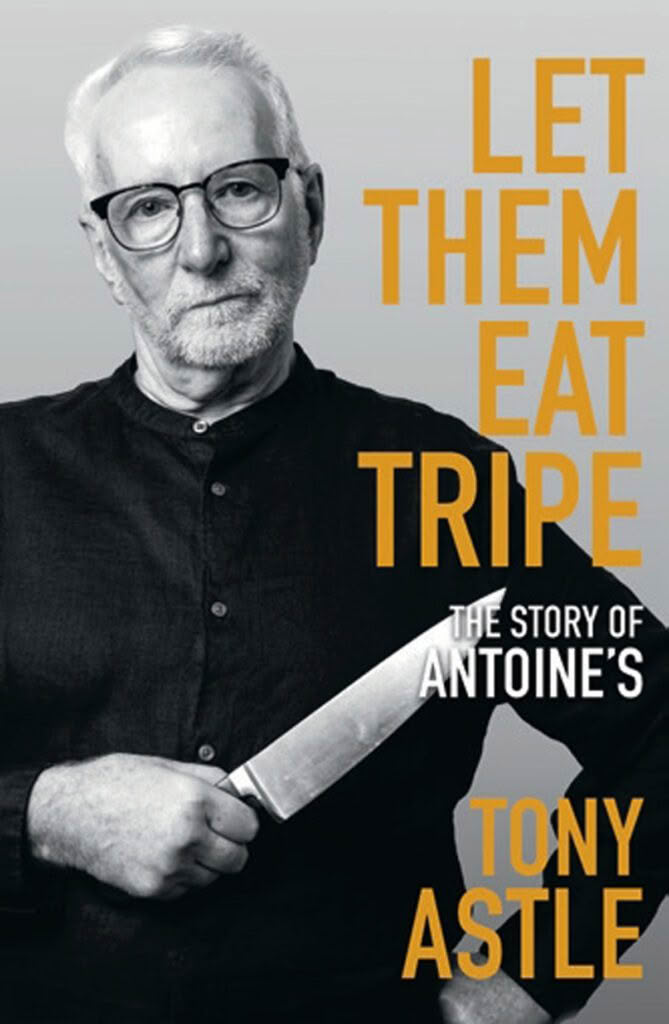

This is an extract

from Let Them Eat

Tripe by Tony Astle,

Bateman Books,

RRP $45. Available

from 7 October.

Photography © Tony

Astle collection.