There is something quietly lovely about squid/wheke (calamari is a type of squid, but that’s not something we want to get into here). It’s a humble, unassuming and forgiving ingredient that with a bit of attention will reward you with something extraordinary. It has no airs or graces, it simply waits for you to bring it to life – for a quick fix, just dust squid rings in seasoned flour and give them a moment in hot oil until they crisp into something golden. A scattering of sea salt, a pinch of chilli flakes, a side of smoked paprika-spiked aïoli and they’re done.

New Zealand squid – often the arrow squid – are harvested primarily off the South Island, in the cold waters off Otago and in the Southern Ocean. It is one of our more sustainable seafood exports and it’s an ingredient that tells a tale of careful fishing practices, caught using trawl methods monitored under the Quota Management System which ensures responsible harvests to maintain healthy squid populations. Squid is particularly suited for this system as it has a short lifespan and reproduces quickly.

TO PREPARE THE SQUID

Historically, it hasn’t always been a seafood superstar. We don’t talk much about squid; we talk about snapper, and we talk about kingfish, yet squid has just quietly been there, not asking for much. For several decades, it was seen as more of a niche item, popular among specific communities but far less so in the mainstream. In recent years, chefs have begun to see squid in a new light, celebrating its delicate texture and clean taste, elevating it from the fish and chip shop to restaurant tables.

Its versatility shines in its preparation, which isn’t complicated. First it needs to be cleaned – outer skin peeled, innards removed and the body cut into rings or strips. Whether served as tender rings in a salad, flash-fried in a light batter, gently braised or cooked slowly in a paella, squid adapts to a bold range of flavours such as garlic, chilli or citrus. Grilling over an open flame with just a touch of olive oil highlights its clean, fresh, subtly sweet taste. The trick is in the timing; it demands either the shortest of sizzles or the longest of stews. Anything in between and it will toughen, curling its way into rubbery defiance.

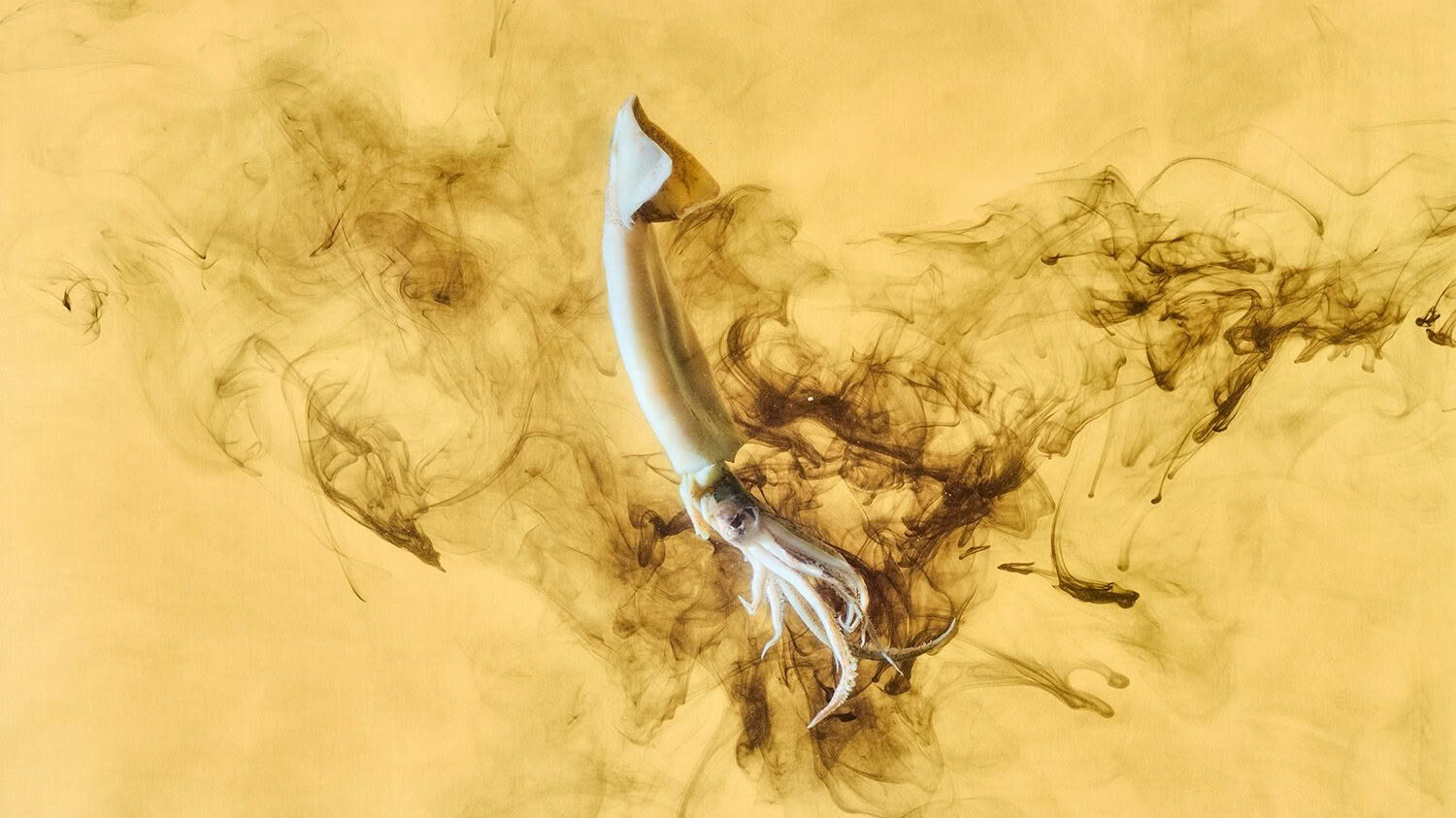

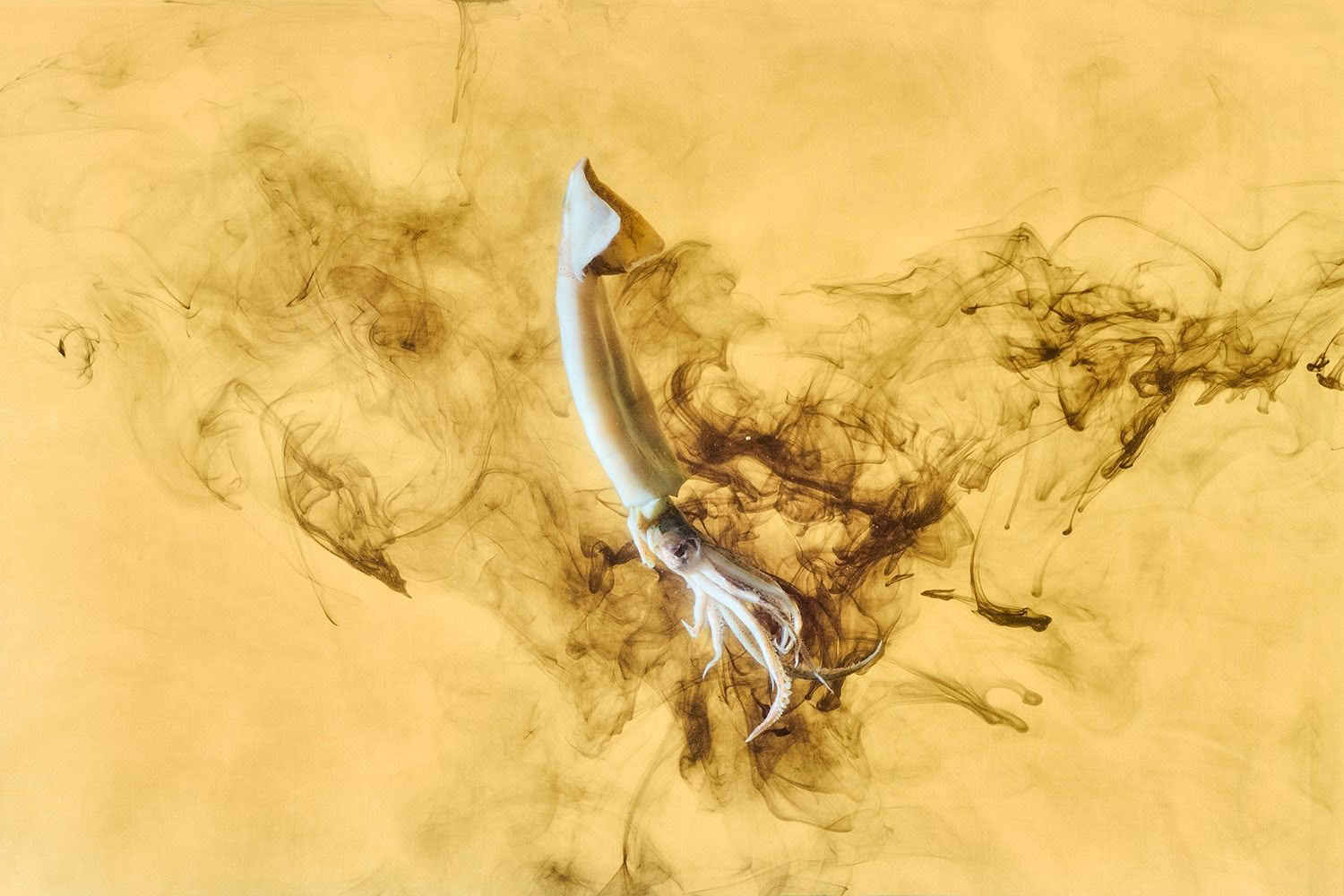

Squid ink is the shade of a moonless night, blacker than black. Stir it into a pot and everything turns dark, like a southerly coming off the Cook Strait. It smells like salt and iron, and it’s what you need to make Arroz Negro, the traditional Spanish paella made with Bomba or Calasparra rice. It starts in a wide, shallow paellera (if you don’t have one, use a frying pan that is wide and flat). Then comes a little oil, a sofrito of onions, tomatoes and garlic, cooked slowly until they’re sweet, the backbone to the dish. The squid goes in, you add the rice, and the ink follows, turning everything dark. The paella simmers, and you leave it be. No stirring, prodding or poking. The rice drinks in the ink, the squid, the broth, becoming something more. Around the edges, the rice starts to stick, turning crisp and caramelised – ‘socarrat’, the Spaniards call it. It’s the heart of the dish, that crackling crust that makes you dig your spoon into the pan until it scrapes.

The first bite is salt and sea, dark and deep, with the faint sweetness of the squid cutting through. You taste the ocean, you taste the ink, that strange, bitter darkness that lingers on the tongue. A squeeze of lemon and the acid cuts through, sharp and bright. It’s a simple dish, but it’s not; it’s everything squid can be, and it’s good. It’s a story of the sea, told in black and white, with a taste that stays with you long after the last grain of rice is gone.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

Give a man a fish… Mussels

Healthy and delicious, sustainable and good value – mussels/kūtai are…

Give a man a fish… Octopus

A staple of Mediterranean cuisine, artfully explored in Japan and a…

Issue 223: Give a man a fish…

Martin Bosley takes the trepidation out of pāua and shares the truth…

Issue 221: Give a man a fish…

Martin Bosley considers what the closure of New Zealand’s scallop…