Mussels/kūtai in their rough green shell are one of the most gloriously compelling eating experiences there is. There’s no place for cutlery here, it’s a sleeves-up, elbows-on-the-table kind of task. The process of extracting a mussel from its shell is quiet, almost ritualistic. The shells themselves, still joined at the hilt, act as natural tongs to help free the flesh from its sanctuary.

It’s a weekend job. I dump them into a colander and give them a rinse under cold water, checking the shells for any that are broken or chipped, knocking off any barnacles and pulling off their Steelo-like beards with a sharp tug down towards the pointed end.

A tap on the counter tests their resolve – only the tightly sealed survive and any that are open and don’t close, I throw out. The team at Marlborough’s Mills Bay Mussels preach raw shucking then cooking for optimal tenderness rather than steaming open first (how to shuck a mussel can be found on their website millsbaymussels.co.nz). The choice is yours. Incidentally, the orange-coloured mussel is the female, the male is the creamy one, though the colour has no effect on taste.

Mussels, versatile as the sea itself, are a crowd-pleaser. Once I have steamed the mussels open, I might add a knob of butter and some chopped garlic to the cooking liquid, or pour in some cider, cream and chopped parsley, or chuck them into a slippery pasta with tomato and garlic. Served with some good crusty bread on the side, nothing tastes better. Or they can be served chilled as part of a seafood platter; mix a teaspoon of miso paste through a cup of store-bought mayonnaise to make a simple yet exotic dipping sauce.

The green-lipped mussel (Greenshell is a trademark name), is farmed in the sheltered cold, clear waters of the Marlborough Sounds, Tasman region, Rakiura Stewart Island and the Coromandel, using no feeds, growth meds or antibiotics – just ropes and patience. It is a wholly sustainable industry. The young mussels, or spat, are placed into long stockings and tied to parallel rows of looped ropes supported by buoys. The mussels grow through the stockings and attach themselves to the ropes, ready to be harvested at about two years old, when the lines are retrieved by boats equipped with giant winches. A mussel is capable of filtering 350 litres of water daily and they are harvested only after the waters have been tested clear of any land-based chemical run-off or harmful biotoxins.

Mussels have a 10-day shelf life after harvest if stored correctly. I put mine into a colander set inside a larger bowl and cover them with a tea towel. I place a cupful of ice on top of the towel and put the colander into the fridge. The melting ice keeps them chilled and sends the mussels into a nice, relaxed state, some with their shell mouths open.

Finally, here’s the thing: our indigenous, green-lipped mussels are recognised as Best Choice under the Monterey Bay Aquarium Seafood Watch, an internationally recognised guide for sustainable seafood. They have a low carbon footprint and are packed full of nutrients. They are good for you. We have an abundance of clean marine waters, an almost benign aquaculture industry and great, affordable mussels because of all of this. Maybe because they are so cheap – about $7.50 per kg – we undervalue them. We eat about 1.5kg per capita per annum, compared to the Dutch at 2.5kg which means there’s room for improvement. I’m doing my bit. It’s your turn now.

SEE MORE FROM CUISINE

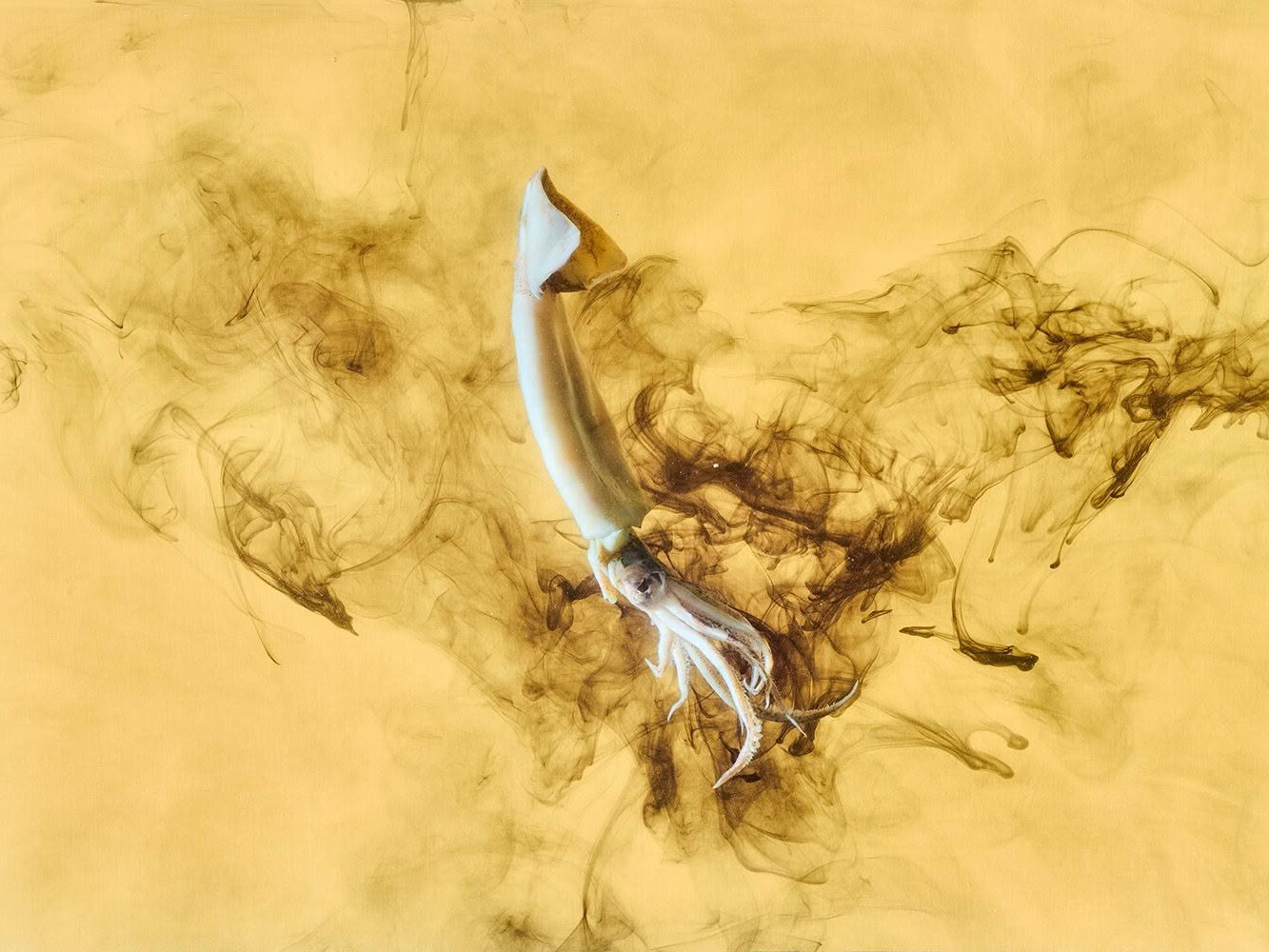

Give a man a fish… Octopus

A staple of Mediterranean cuisine, artfully explored in Japan and a…

Issue 223: Give a man a fish…

Martin Bosley takes the trepidation out of pāua and shares the truth…

Issue 221: Give a man a fish…

Martin Bosley considers what the closure of New Zealand’s scallop…